Top Tools for the Home Engine Builder

Want to build engines at home like the pros? Here are the tools you’ll need to do the job.

Many years ago, we bought this set of Fowler mics, but we rarely measure anything larger than 4.50 inches. We mainly use the 2.00–3.00 mic for measuring crank journals, so that might be a good place to start.

When doing any measurement, first establish if the mic is accurate by testing it against a standard. These blocks came from a retired machinist. Each block is accurate at 68 degrees to 3 to 5 millionths of an inch (0.000003 to 0.000005 inch).

It’s best to establish a procedure when measuring journal diameters with a micrometer and then always perform the job the same way. It’s also best to take multiple measurements on each journal for runout and accuracy.

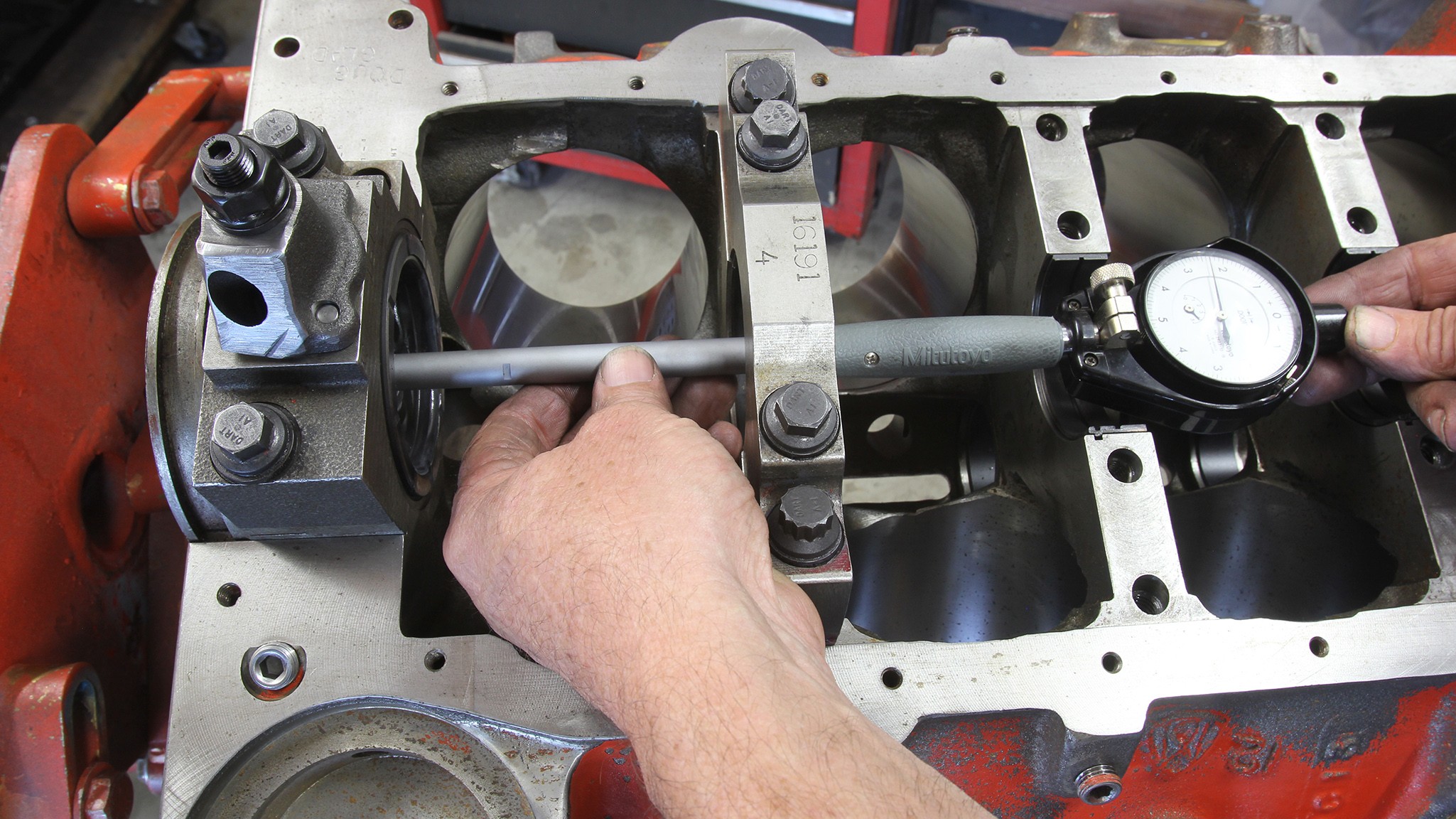

This is the Mitutoyo dial bore gauge we’ve used for years. We treat it with respect and store it carefully. It often reveals what we don’t want to know, but at least we know the numbers are accurate. Good tools always make the job much easier.

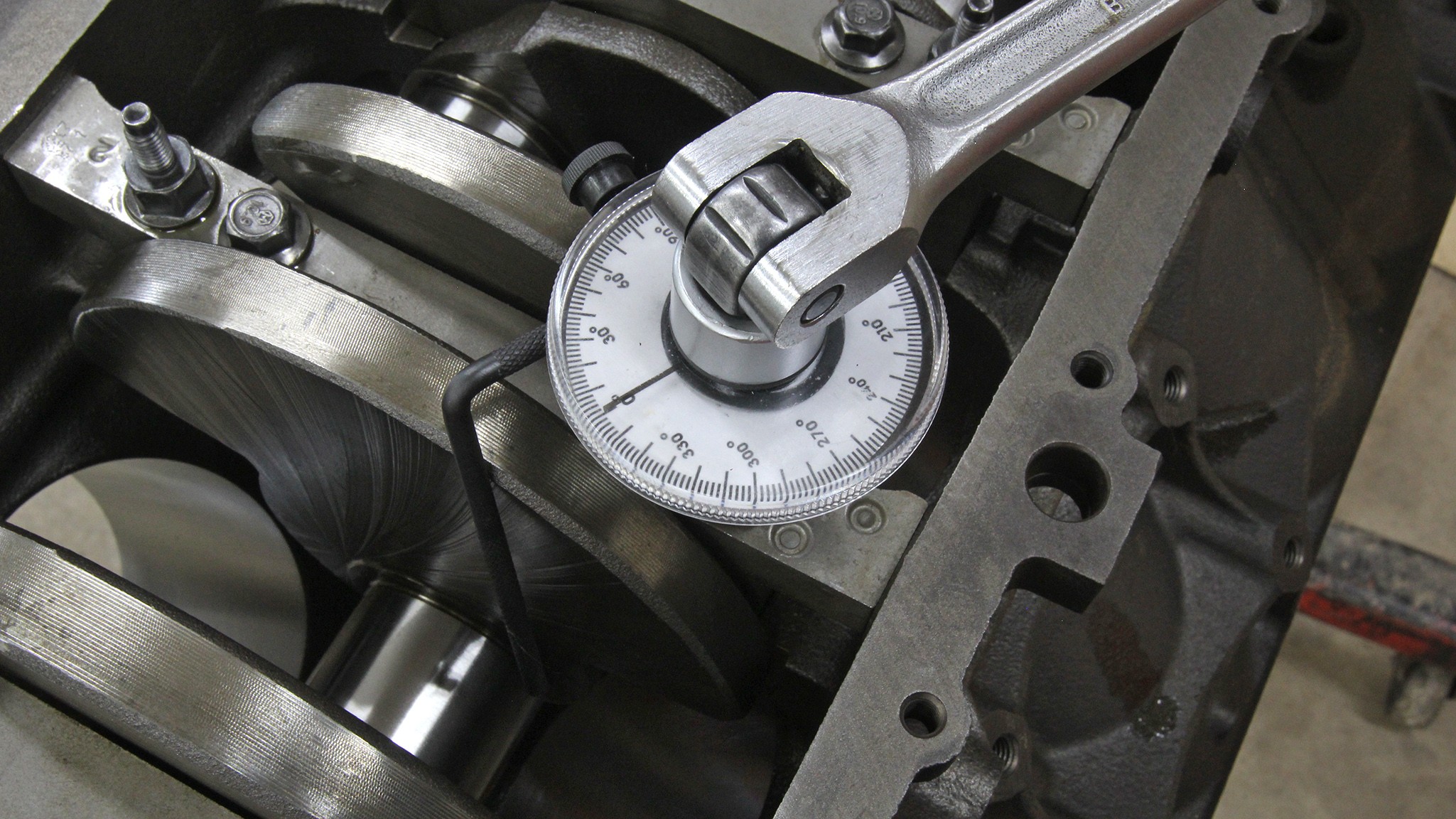

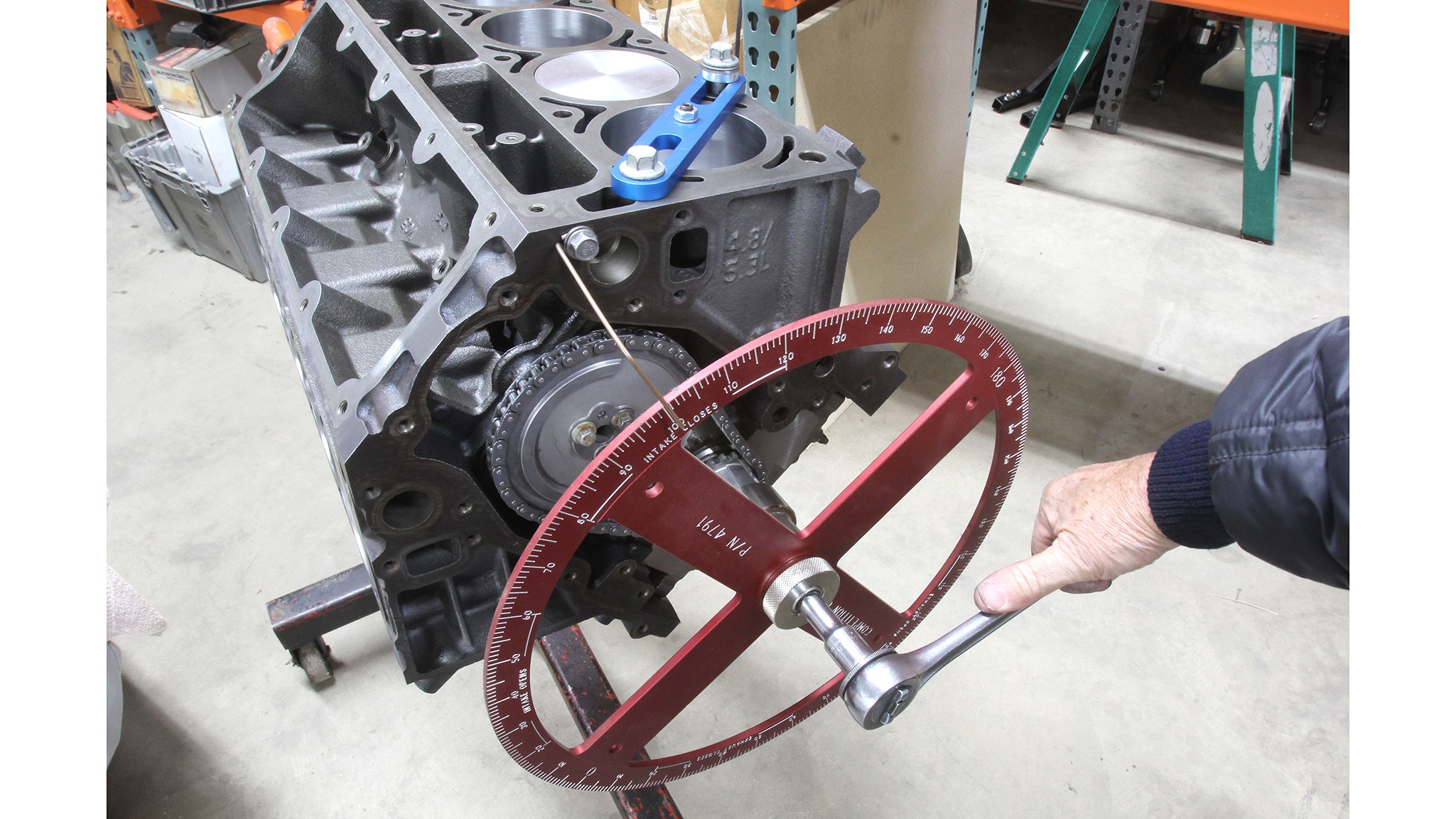

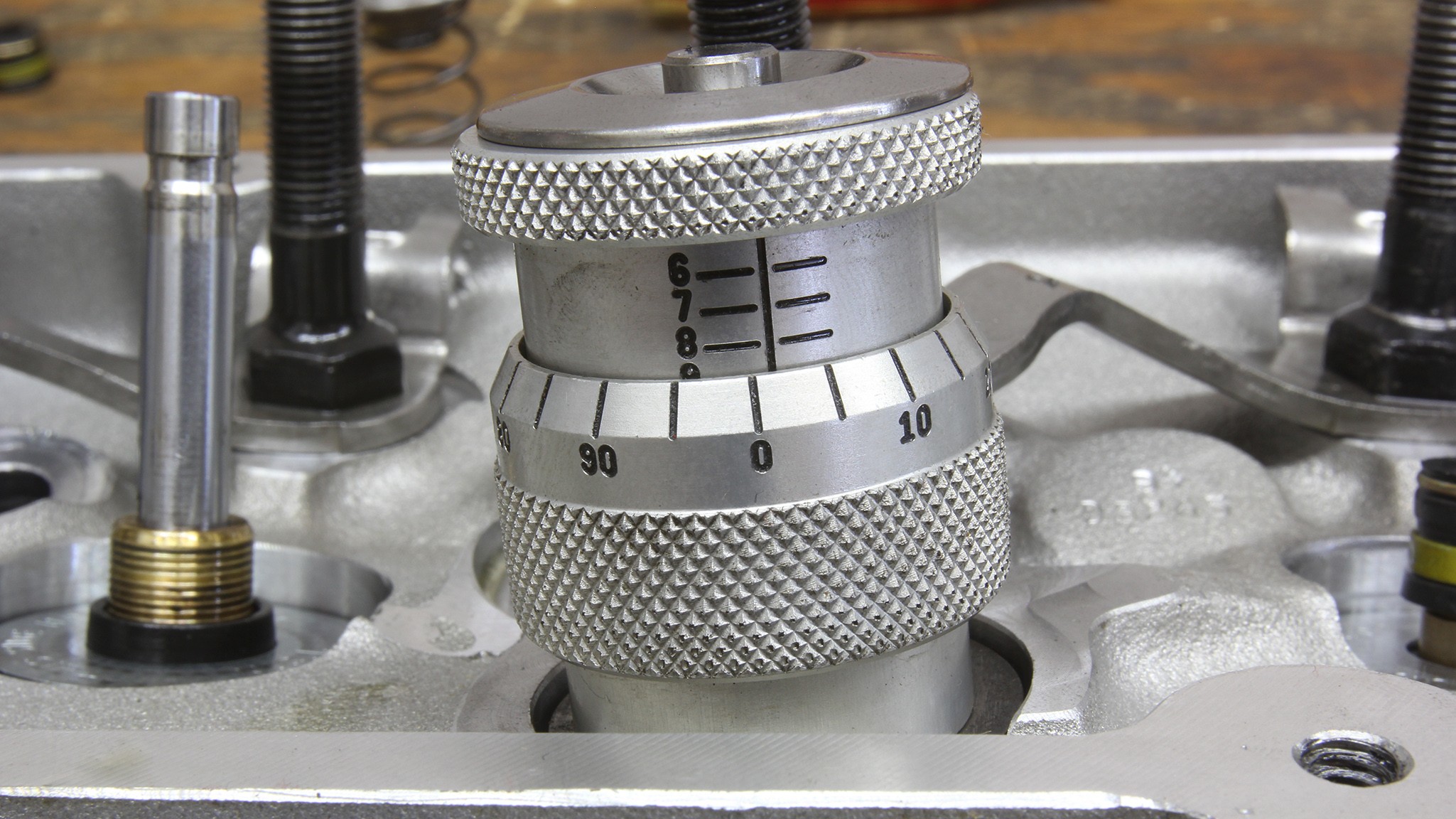

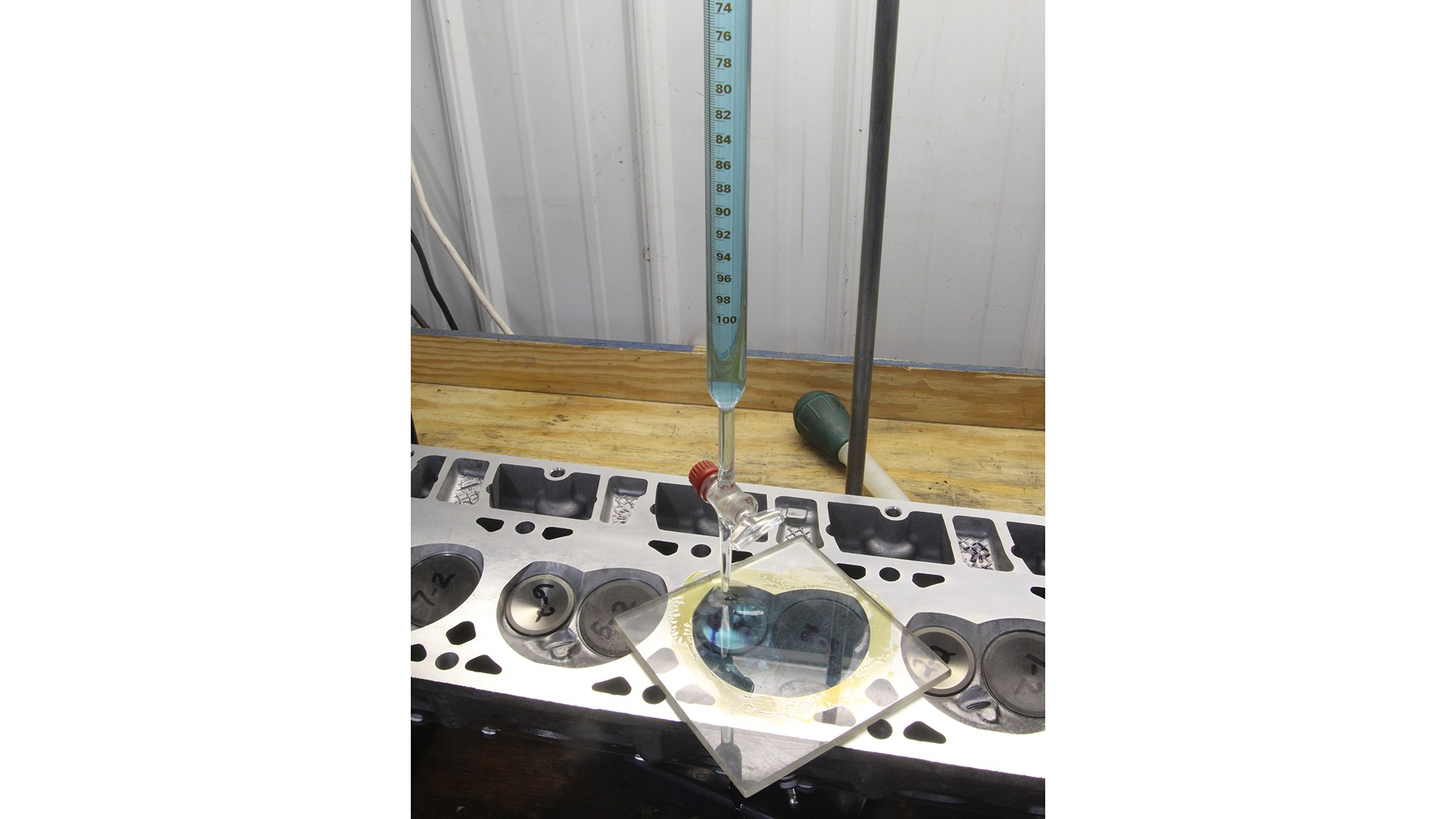

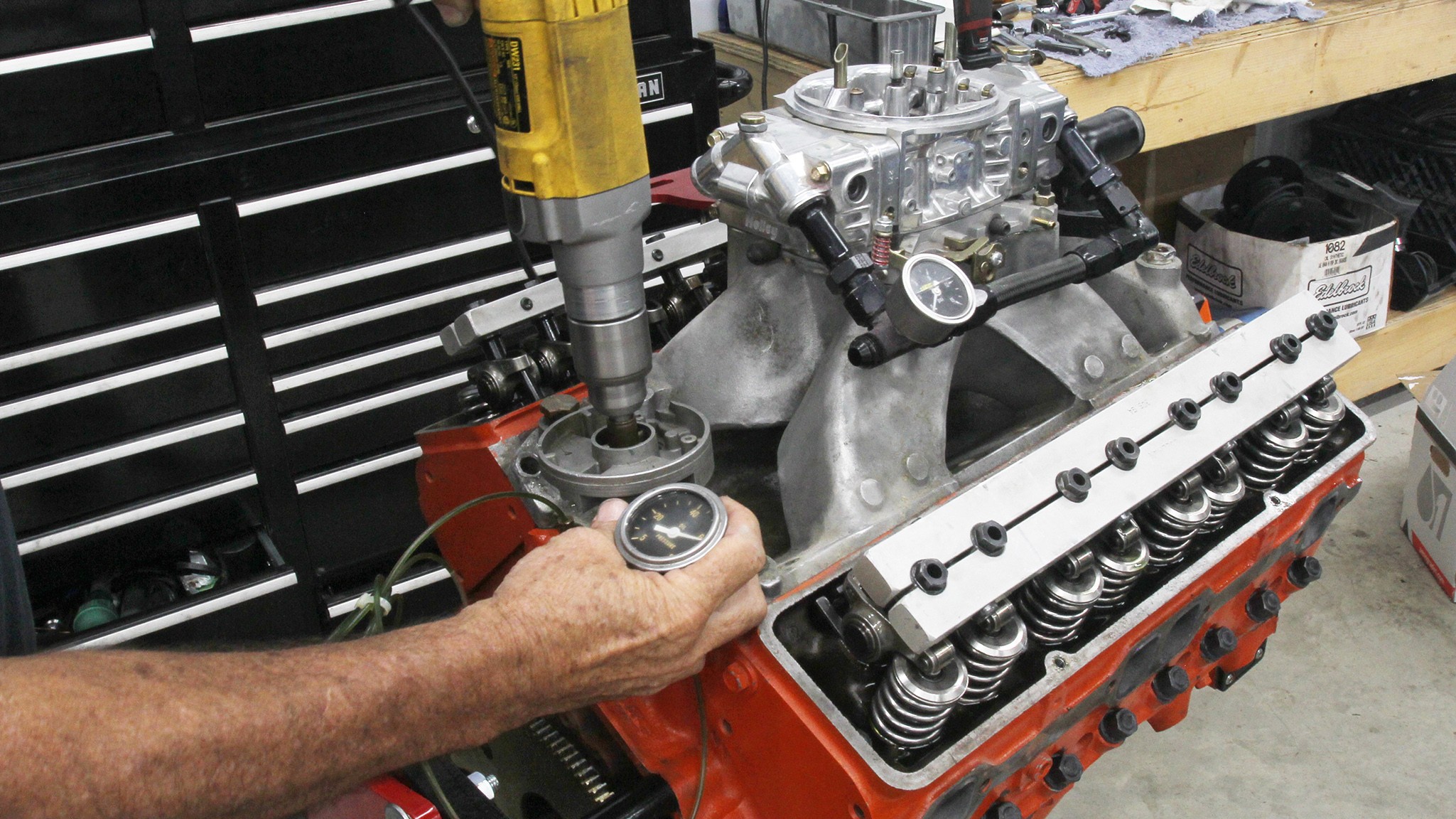

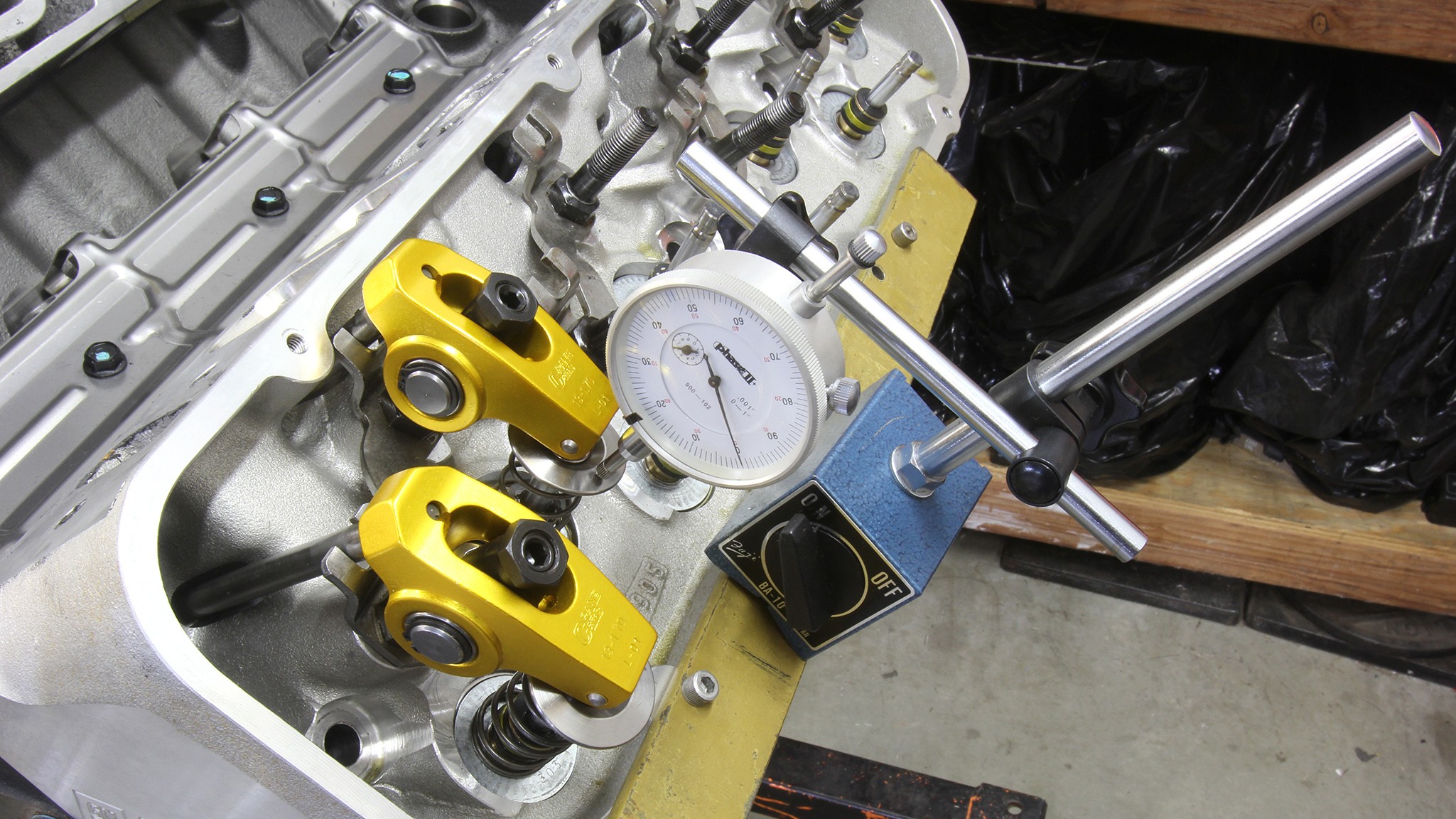

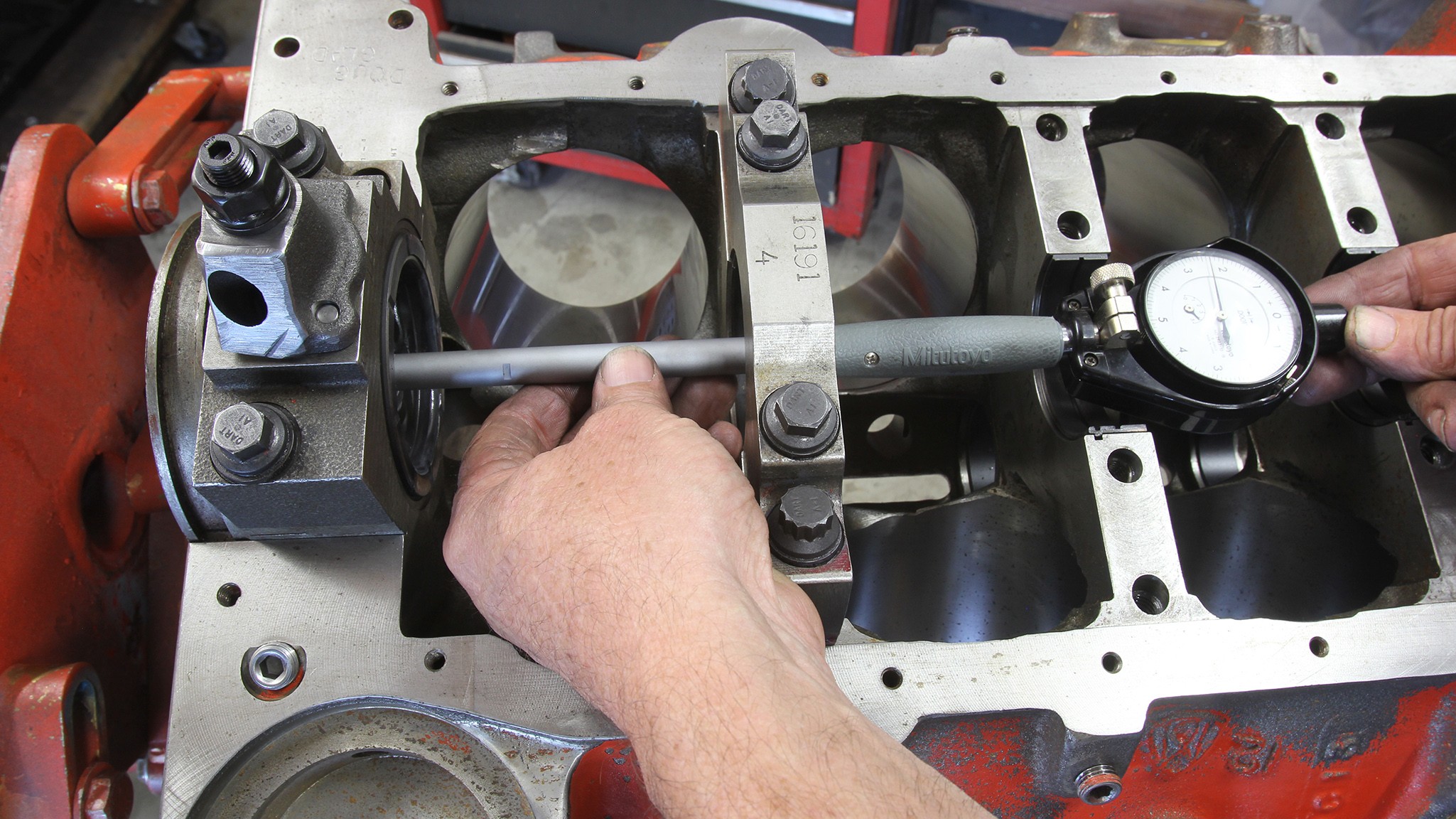

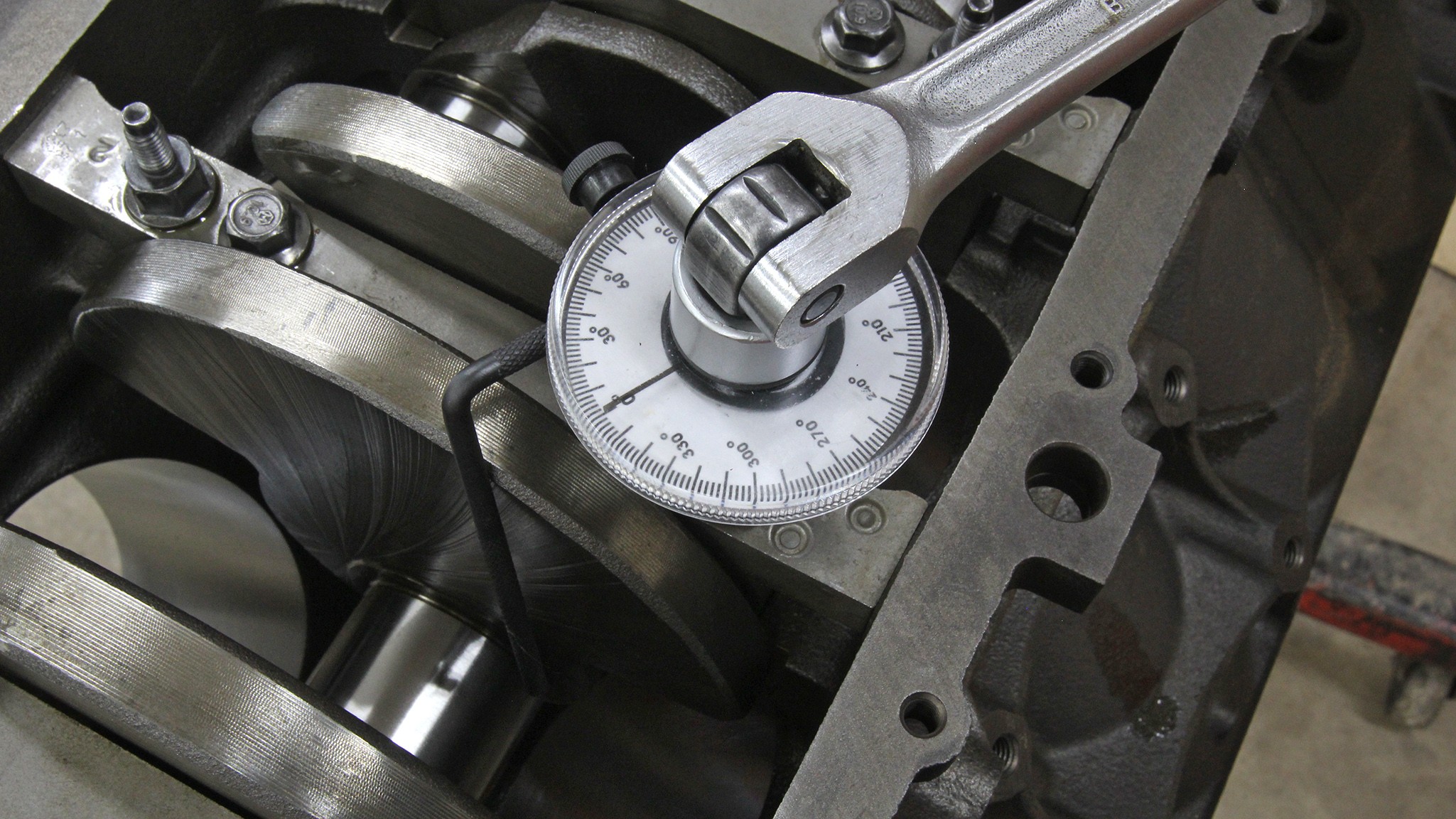

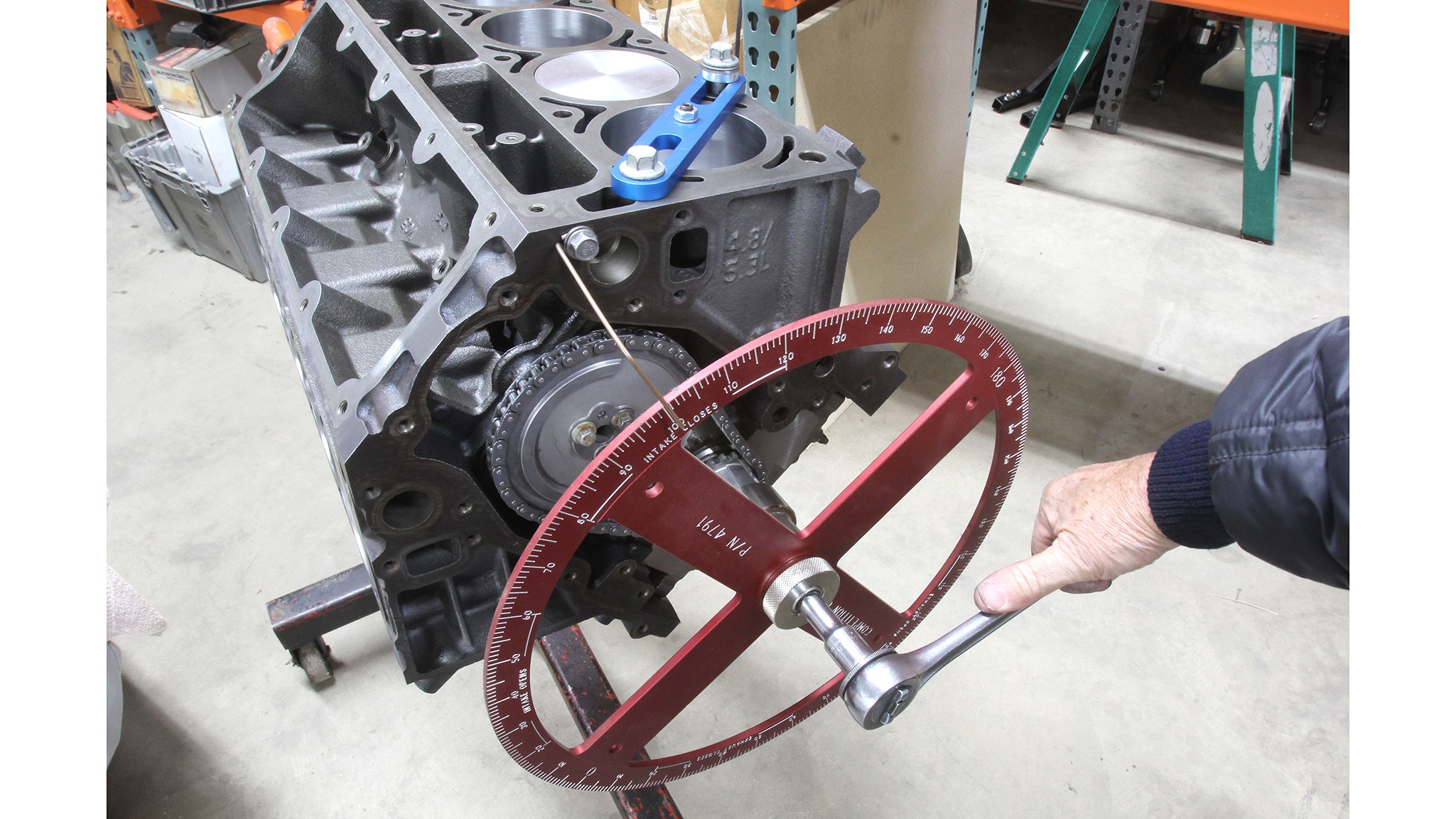

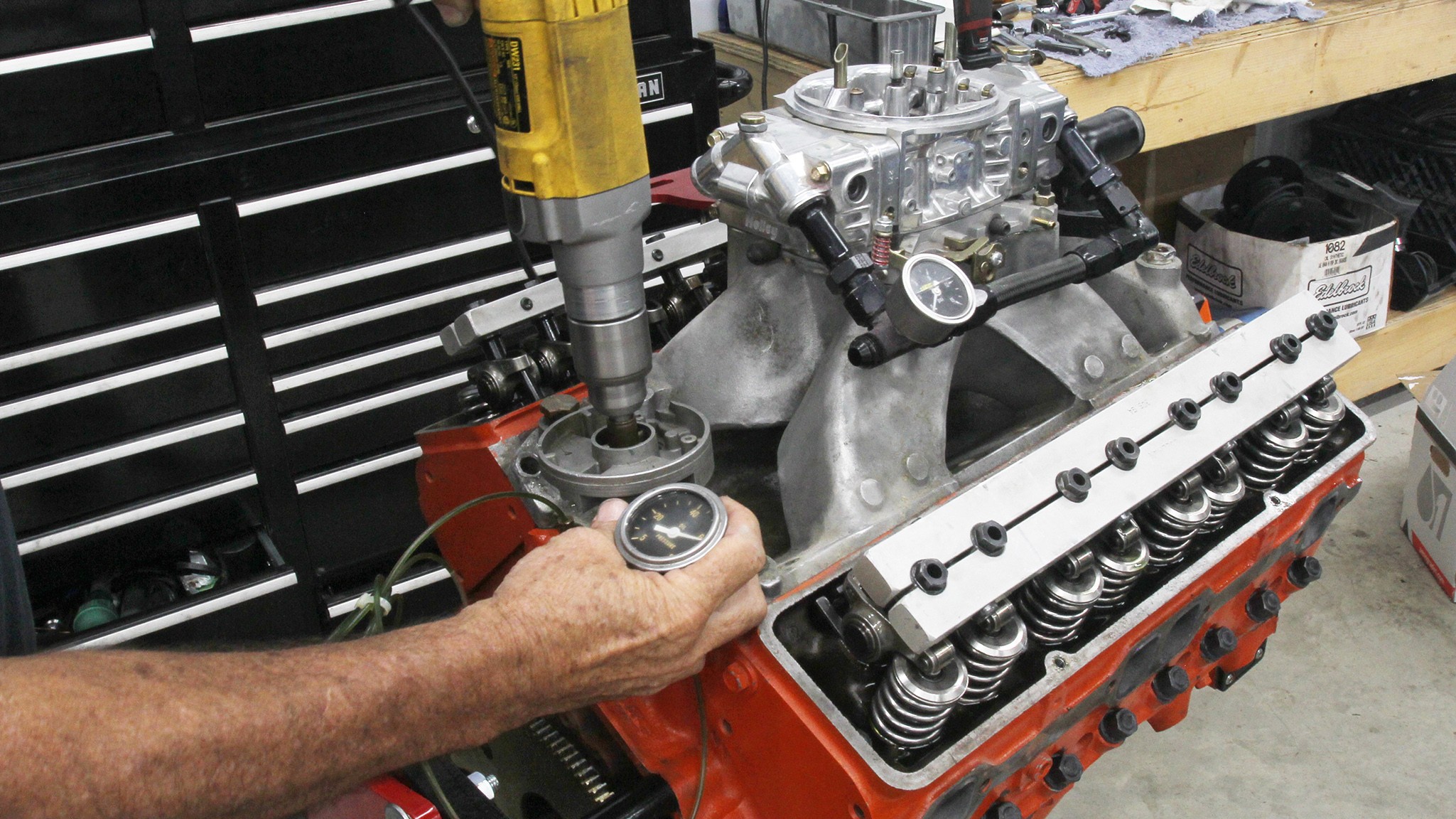

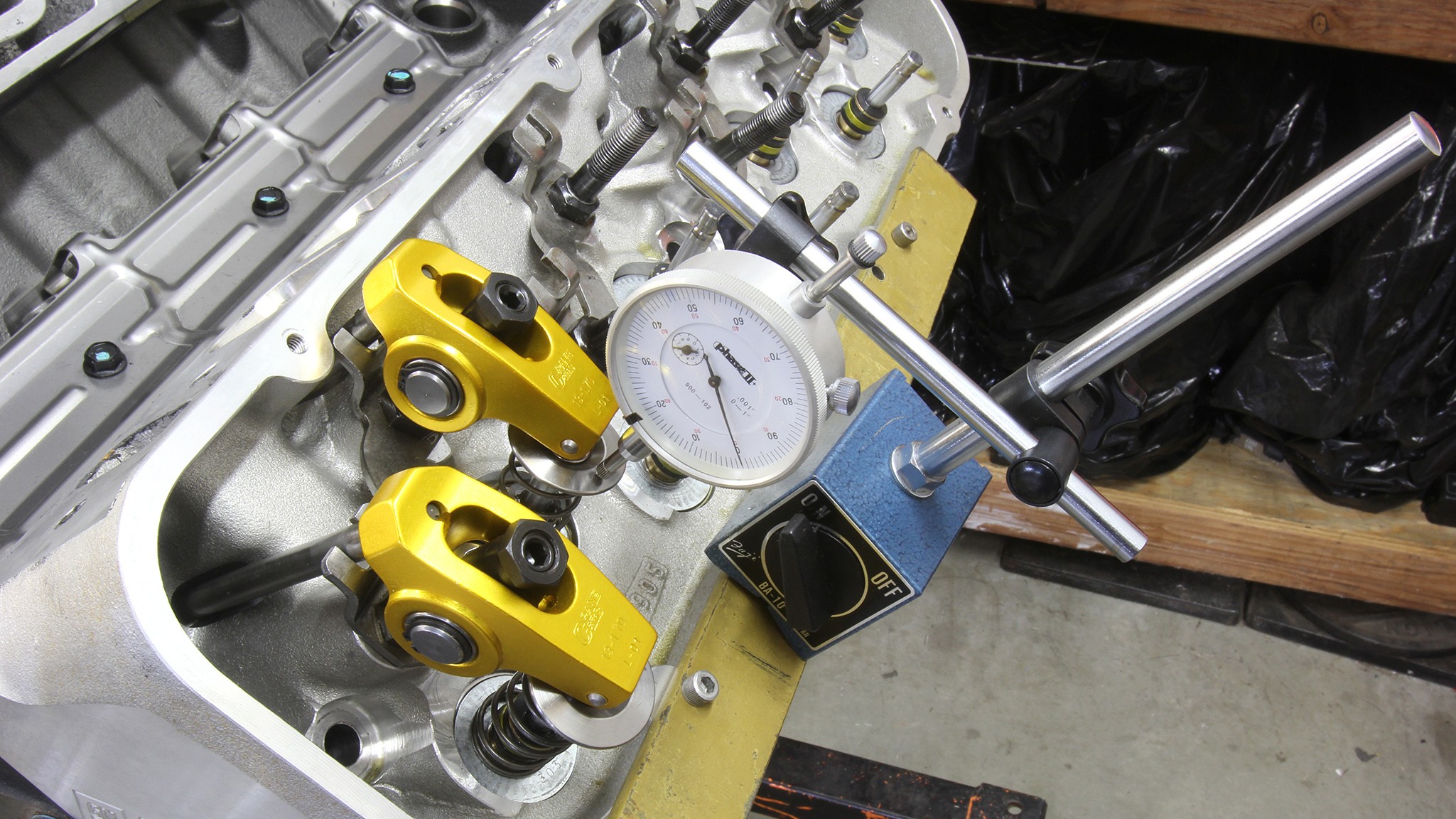

There are multiple engine-building operations that require a dial indicator mounted on a magnetic base. Crank and cam endplay, cam degreeing, and piston-to-valve clearance are a few of the major uses for this tool. Look for an indicator that offers at least 1 inch of travel with accuracy to 0.001 inch.

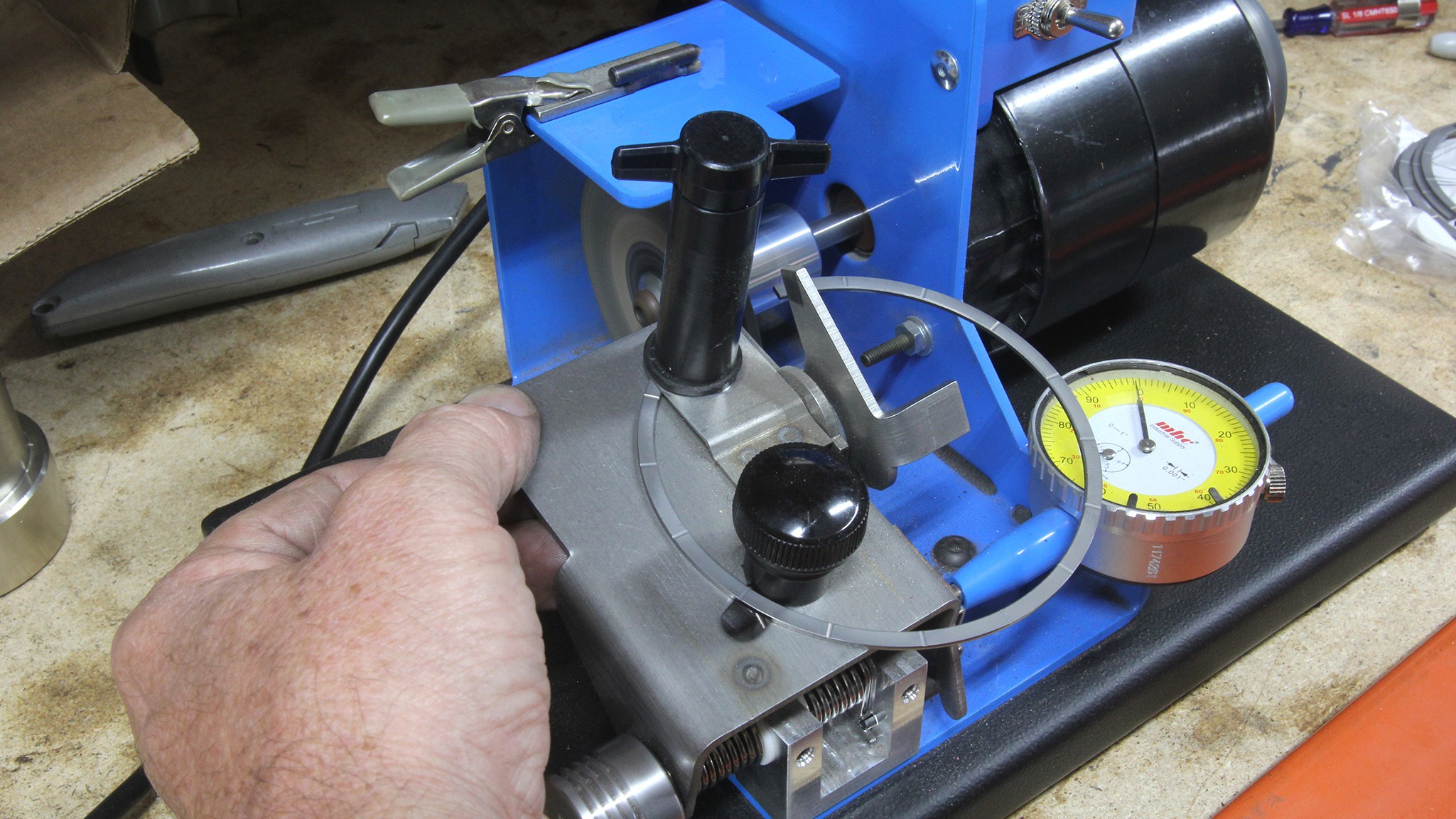

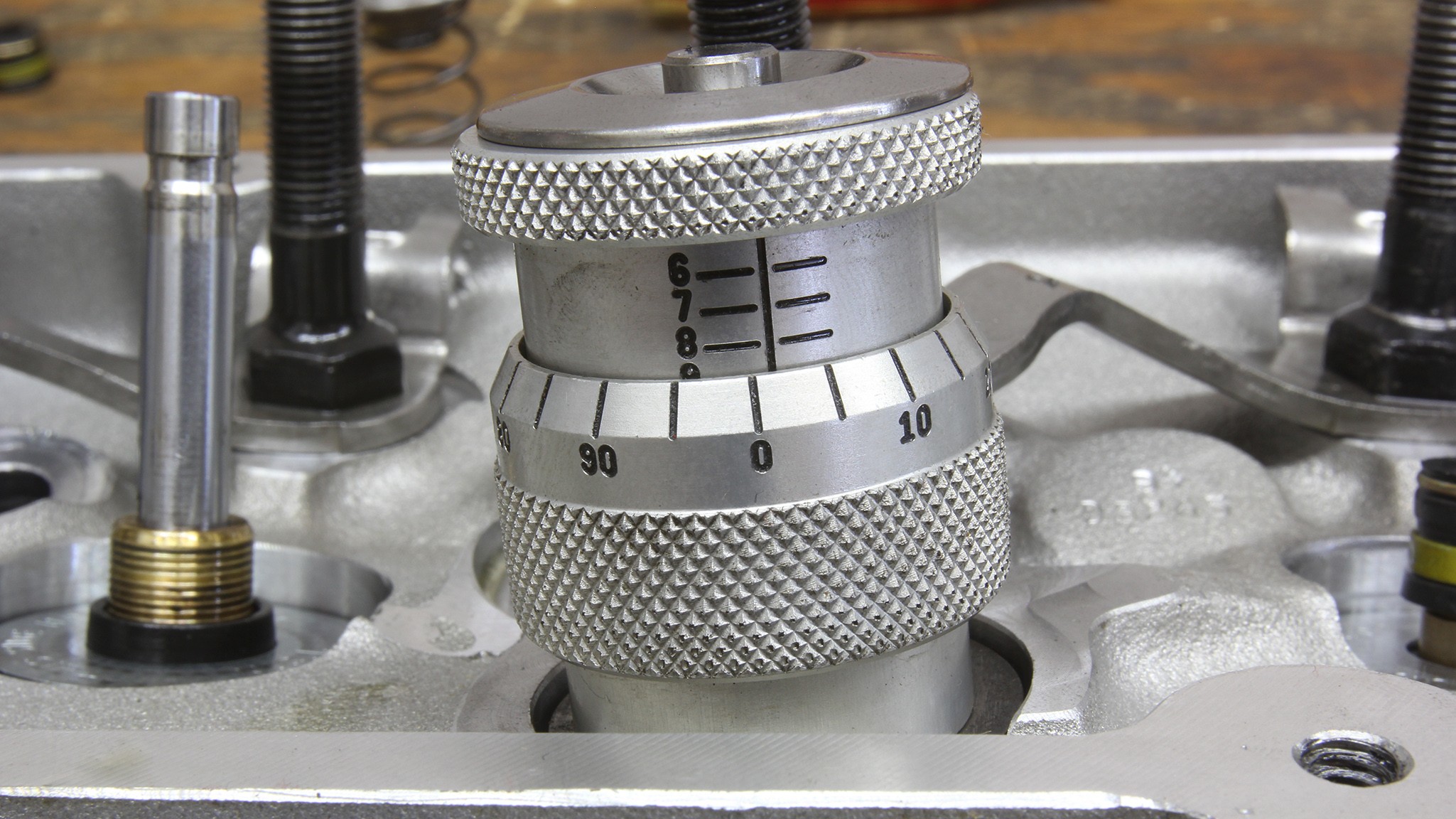

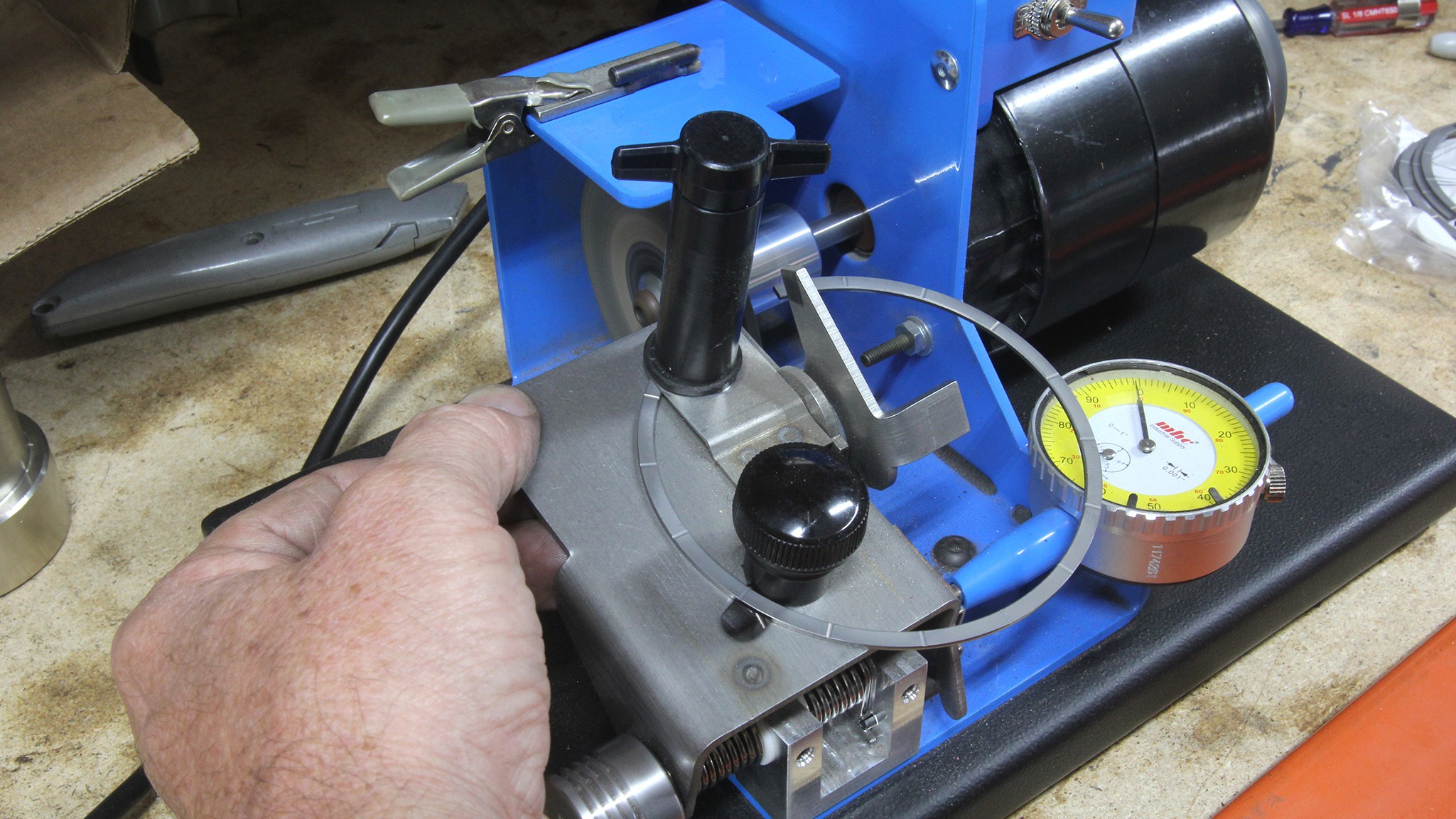

Manual ring grinders work great, but it does take time to set 16 individual rings. This electric ring filer from Summit can do the job in one quarter of the time it takes with the manual tool. When using the manual tool, always turn the handle counter-clockwise.

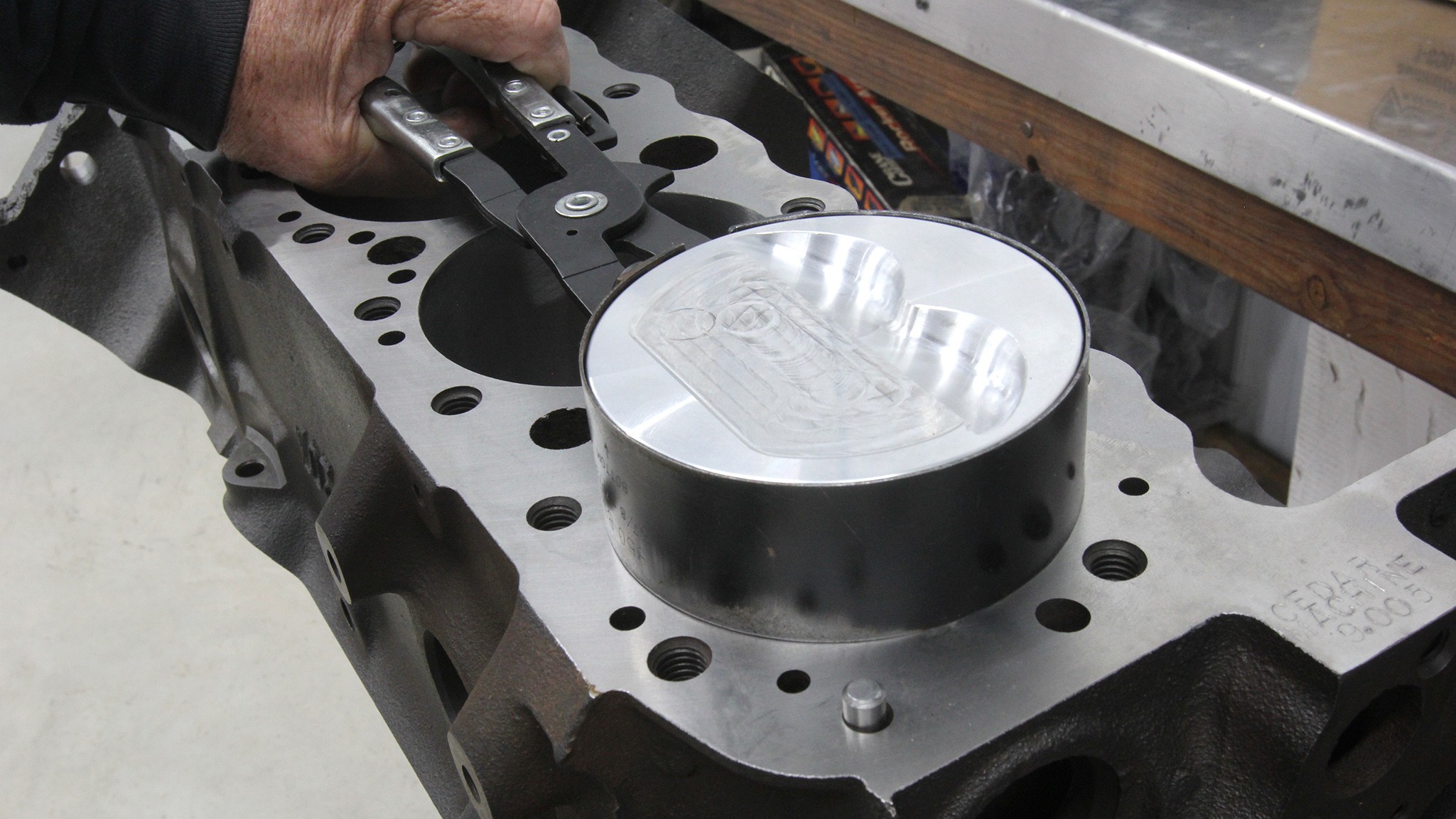

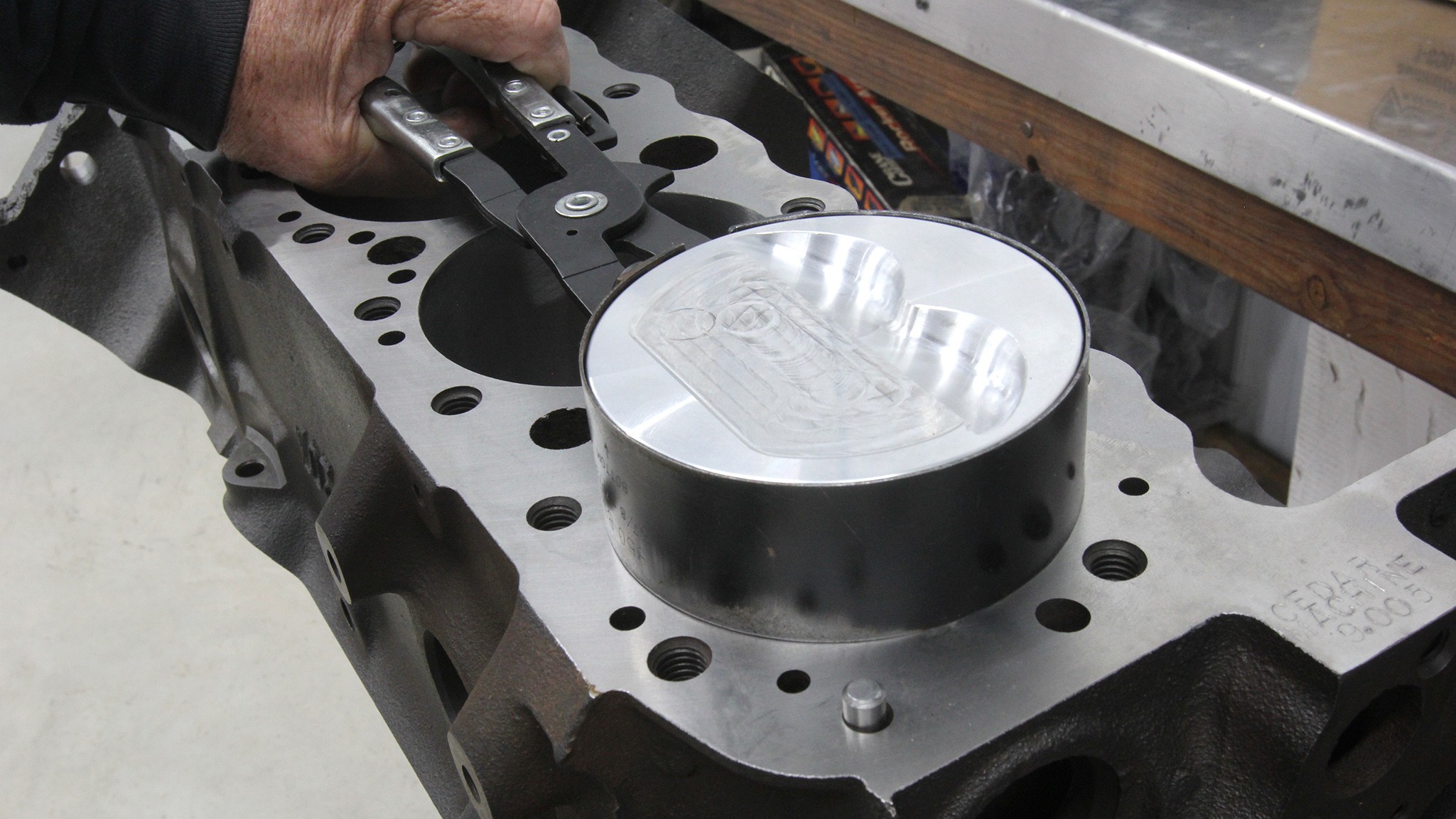

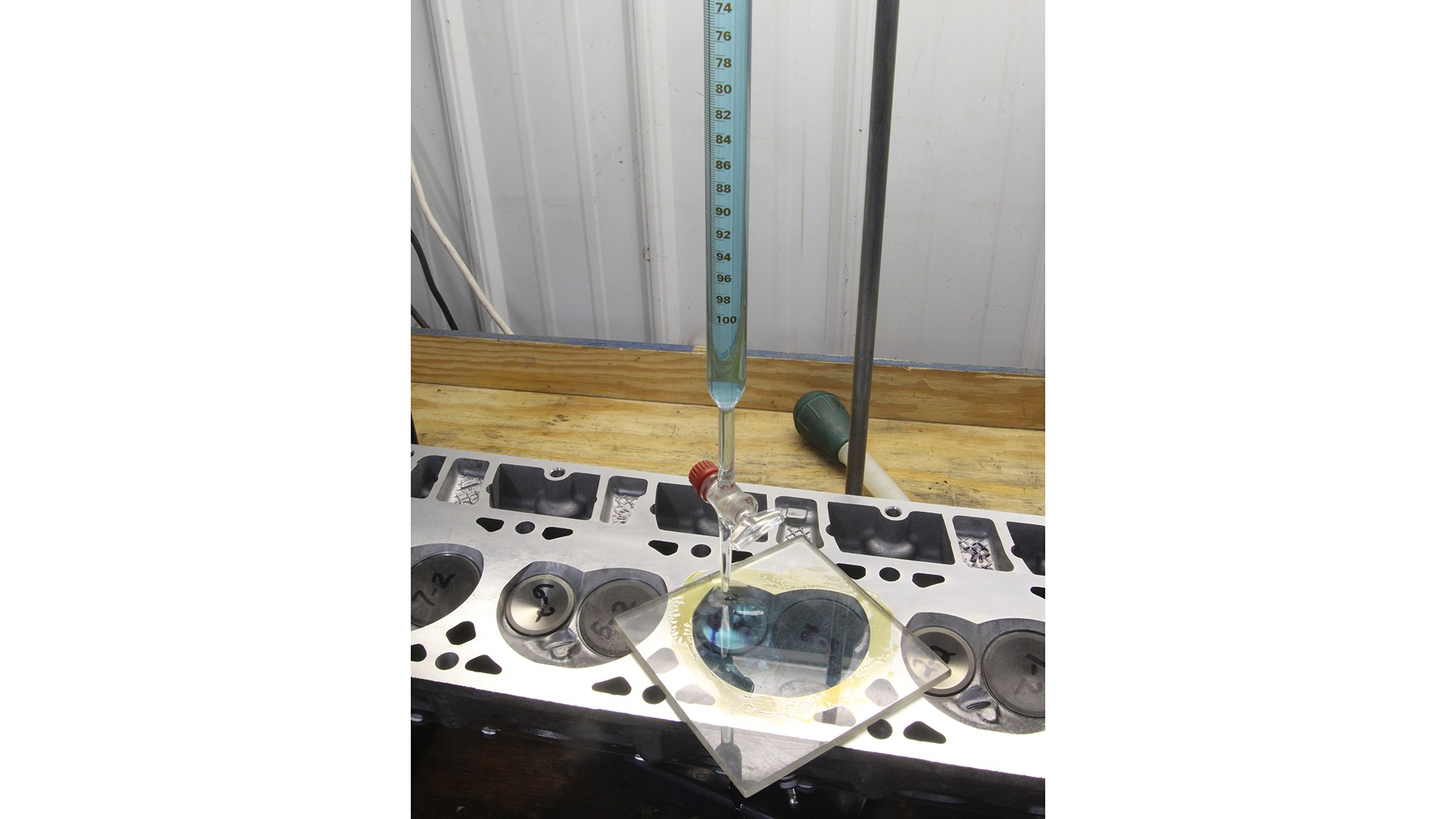

You can buy an inexpensive universal piston ring squaring tool, but before they were available, we used an old flap-top piston with a ring in the second groove. We invert the piston into the bore, and it pushes the ring down about 3/8-inch from the deck and squares the ring against the top of the piston. Then we can quickly check ring end gap.

(1 / 21)

Many years ago, we bought this set of Fowler mics, but we rarely measure anything larger than 4.50 inches. We mainly use the 2.00–3.00 mic for measuring crank journals, so that might be a good place to start.

When doing any measurement, first establish if the mic is accurate by testing it against a standard. These blocks came from a retired machinist. Each block is accurate at 68 degrees to 3 to 5 millionths of an inch (0.000003 to 0.000005 inch).

It’s best to establish a procedure when measuring journal diameters with a micrometer and then always perform the job the same way. It’s also best to take multiple measurements on each journal for runout and accuracy.

This is the Mitutoyo dial bore gauge we’ve used for years. We treat it with respect and store it carefully. It often reveals what we don’t want to know, but at least we know the numbers are accurate. Good tools always make the job much easier.

There are multiple engine-building operations that require a dial indicator mounted on a magnetic base. Crank and cam endplay, cam degreeing, and piston-to-valve clearance are a few of the major uses for this tool. Look for an indicator that offers at least 1 inch of travel with accuracy to 0.001 inch.

Manual ring grinders work great, but it does take time to set 16 individual rings. This electric ring filer from Summit can do the job in one quarter of the time it takes with the manual tool. When using the manual tool, always turn the handle counter-clockwise.

You can buy an inexpensive universal piston ring squaring tool, but before they were available, we used an old flap-top piston with a ring in the second groove. We invert the piston into the bore, and it pushes the ring down about 3/8-inch from the deck and squares the ring against the top of the piston. Then we can quickly check ring end gap.